We should all be a little more considerate before tearing a footballer to pieces.

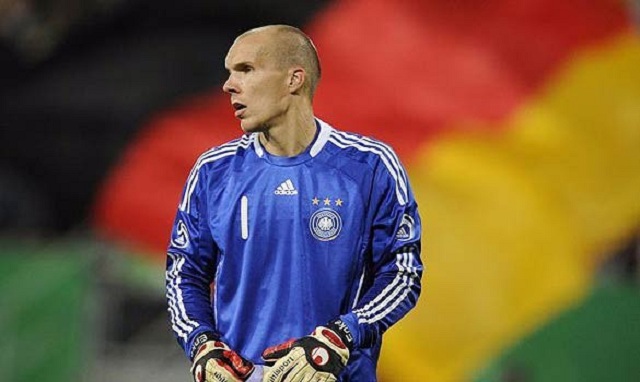

On 10 November 2009, Robert Enke committed suicide. At the time of his death, he was widely considered to be a leading contender for the German number one spot at the 2010 World Cup

Back in 2002, Barcelona goalkeeper Robert Enke arrived at the Camp Nou stadium for a Champions League match against Leverkusen. When he entered the locker room, he found out that he wasn’t on the team sheet for the game. As he made his way outside, he had no idea how to get back home – he completely forgot about the existence of taxis and buses – so he just stayed there.

Enke was rarely a starter for Barcelona. His most notable performance there came in an embarrassing loss to 3rd division team Novelda, when he made 2 critical errors that led to the team’s exit from the Spanish cup. This led to a lot of criticism in the media about his ability. Since then, he played only a handful of matches for the club. Despite that, he was the team’s regular 2nd goalkeeper – that’s why he was so distraught about not being selected for the match against Leverkusen. In the world of football, where people often find out about changes from the media rather than by a face-to-face conversation, this is a way to signal to a player that he is no longer wanted in the club.

Enke tried to keep going after this incident. He showed up to practices and trained with the team, until he was sent to Turkish side Fenerbahçe. That’s where he suffered his first spell of depression, the illness that would eventually lead him to end his life.

The book about Robert Enke’s life, titled “A Life Too Short: The Tragedy of Robert Enke”, is one of the best books written about football in recent years. In it, author Ronald Reng tells the story of the goalkeeper’s troubled life, focusing on how he (and people around him) tried to deal with depression.

A survey by FourFourTwo magazine finds that 70% of footballers in England and Scotland think that depression is a common problem among footballers. Many of them say that they have suffered from it themselves.

Modern medicine is still unable to pinpoint the causes for depression. Many experts have suggested different reasons, such as changes in family structure, urbanization and the lack of community in the western world.

One thing is certain though – when depression sets in, it isn’t necessarily just a mental illness, but a physiological issue. When you examine the brain of a person suffering from depression, you can see parts of his brain are inactive. Depressed patients often say that their life is “surrounded by darkness”, and that they cannot think positive thoughts. Patients usually suffer from prolonged periods of unhappiness, low self-esteem, and are usually in a state of profound sadness and despair.

It seems like the health of football players who suffer from depression is much quicker to decline than in other professions. It’s possible that depression has a bigger influence on a player’s health than, say, knee issues.

Football players, who tend to experience quite a few mood-swings in a season, are usually under a lot of stress to perform. This makes them much more susceptible to depression. Enke himself once told his agent that “football turns you into a person that is never satisfied. You always want more”. This constant chase is not healthy for the human brain.

“The best way to deal with it is to leave the game and get help”, said an unnamed League One player in England. The problem, as told in Reng’s book, is that leaving the game is very difficult for a football player. These guys trained their entire lives to play football – what can they possibly do without it?

There is also another major problem. “Enke’s death influenced a lot of people because they felt that the values he believed in, such as solidarity and empathy, were denied of him in professional football”, wrote Ronald Reng. “Robert and other players suffered from it, because they could tell that most managers, and sometimes even the public, view these values as a sign of weakness in a footballer”.

Once, when he was told to be more ruthless in his quest to become the national team’s starting goalie, the German shouted back “I’m not like that, and i will never be like that!”.

“The Secret Footballer”, an un-named professional football player that writes eye-opening columns for “The Guardian”, wrote about his own struggles with depression. “I have only ever found football to provide me with any great joy in the immediate aftermath of winning a game”, he wrote. “Winning says ‘I’m better than you and the lads that I play with are also better than you’. It’s a playground mentality, deep rooted in us, that comes racing to the surface in the wake of a success. But losing a football match is a terrible feeling and, worse, being responsible for that loss with a mistake feels as if the whole world is pointing at you and laughing while taking pot shots at your stomach”.

A depressed football player doesn’t have a lot of places to turn to for help. It’s almost impossible when the game is so “public” – the speculations, the media, the fans, the rumors, the discussion forums. What would you think if you found out that your team’s captain is suffering from depression? Would you still want him as a captain?

Robert Enke should have been admitted to a clinic. He refused to go, because he was trying to secure his spot in the national team’s starting line-up for the upcoming World Cup. Would he still have a shot if he was getting help for a “mental illness”?

When Enke’s wife Teresa tried to convince him to go and get medical help, he asked her “How can a goalkeeper have mental problems?” She answered that “in these clinics, there are many different people. Lawyers, professors, businessmen – it’s a difficult thing for everyone”. Enke responded “it’s different for me. If the public finds out that these people have a problem, it’s not so bad for them”. The discussion ended in silence, and a few weeks later Enke committed suicide.

In England, depression among footballers became a legitimate topic of discussion following former Wales manager Gary Speed’s death. Celtic Manager Neil Lennon and ex-player Stan Collymore admitted that they, too, suffered from spells of depression. Several other players did the same. Former England squad member Darren Eadie plans to set up a special clinic for football players who suffer from depression, and the Professional Footballers’ Association in England also tries to support those who try to cope with the problem. The subject is no longer “taboo”.

In Germany, this topic is also talked about frequently, following Enke’s suicide and Sebastian Deisler’s retirement.

Deisler, who was hailed as the future of German football at the turn of the millennium, retired at the age of 27 due to a combination of injuries and depression.

Sometimes we tend to forget that a lot of footballers are very young, and sometimes not completely mature. When you consider the amounts of money that some of these guys receive, it’s no wonder that many of them develop addictions or suffer from different mental issues.

They say that depression is the epidemic of the 21st century. According to researches, about 16% of the world population will eventually suffer from some kind of depression. While football fans are less susceptible to suffer from depression – according to research, this is due to the sense of community created by following the game – players are much more vulnerable because of the great stress, publicity and money in the game.

This means that maybe we – fans, journalists, executives and even coaches – should be a little more considerate before tearing someone to pieces. We just might need to watch our words before passing judgment on a goalkeeper who made a mistake. We need to be a little more sensitive.

by Ouriel Daskal from Soccerissue , you can also follow him on twitter @Soccerissue and on Facebook

Pingback: Gclub()

Pingback: http://www.isaacmass.com()